Make Every Golf Hole as Strategic as Possible

NEW COURSE

DESIGN

"Richard was very willing to listen to everyone involved in the project. This was a quality I did not see in other Architects I interviewed and proved to be an invaluable asset to his success.”

- Chuck Clancy, Creekside Golf & Country Club

Golf Course Design & Routing: The Arrangement of a Series of Golf Holes On the Land.

The Land

The land is the single most important element for the creation of a great golf course. The origins of the game began with people swatting objects along the ground, adapting their thought process and decision-making as they encountered each land form. That is the essence of the game of golf and that is the reason why golf has such a grasp on people. The great golf courses of the past - The Old Course, North Berwick, Dornoch, Sunningdale in the British Isles, Cypress Point, Pine Valley in the United States - all derive their character and strategy from the grounds on which they are placed.

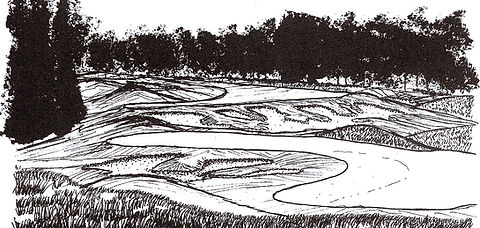

Inspiration of the Ground

The ground's character must determine the style, location, and direction of a golf hole. Natural flats and ridges for landing areas, existing saddles, ridges, and plateaus for greens; knolls and shelves for tee boxes are all land forms which I seek out in walking over a piece of ground. Intense study of the topography goes a long way in creating character in a golf course routing as well as natural drainage patterns and economy. Great golf courses and affordable construction truly go hand in hand with the proper execution of a golf course routing. Slowly over time the art of the golf course routing has been whittled away, replaced by an increased reliance on earthmoving equipment. This may come about from laziness of the golf course architect, simply a lack of creativity overcome by the ability to move dirt, or it could simply be a drop in expectations from golfers and architects alike. Nonetheless, the direct consequence is a monotony of land forms found in repetition across the world's golf courses, leading to a lack of creativity and memorability but an excess in artificiality and boredom. Somewhere along the line the modern golf course architect has replaced detailed study of each contour of the ground with the desire to create something that has already been built elsewhere. It makes zero sense to alter a piece of ground that is unique to the earth to simply transform it into a feature found somewhere else.

Form Follows Function

At one point in the evolution of the golf architecture profession, the land stopped influencing the game and its implements. Instead, the implements and the game began to influence the land and the golf course designer compensated by altering that land. Although sometimes the alteration of the ground is necessary, for the most part the effort has grown into an unnecessary step in the design process rooted in an Architect's desire to impart specific pre-conceived notions developed elsewhere on the task at hand. This unfortunate development has fractured the most important principle of all design (not just golf course design) --Form Follows Function. Form following function in its most basic form means that design happens as a result of specifically solving a problem, not just for ornamentation's sake. Unfortunately, many golf course architects today ignore the beauty of the land as it lays, choosing instead to create features which may impress the eye from an artistic standpoint. These design decisions do not provide the basic function of the game of golf (strategic enjoyment) without excessive effort. The ability to route a golf course is predicated mostly on following the 'form follows function' maxim. The golf course architect must analyze elements of a site and match those elements with the various golf course features required for a golf course routing. The great golf architects of the past sought out the correctly-sized plateaus for green sites. Smaller areas better presented themselves as tee sites and the broader flats were most appropriate for landing area sites. When I walk a site and then study a topographic map, I seek out the broadest spaces for landing areas of the longest holes to ensure a natural appearance, plenty of distance, and ample width for fair play. Extreme slopes are often incorporated as strategic challenges for players off the tee, in front of landing areas or protecting greens. These slopes are advantageous in between holes as well. The most severe ground is reserved for a heroic shot or to connect a tee and green for a short par-four or a par-three hole. In the art of golf architecture, the form of the land will determine the function of a golf hole, strategy, or hazard. Not only will the results be the most naturally-appealing to the eye, but well-draining and cost effective as well.

Instinct and Randomness

Instinct and Randomness are two words which most people may not associate with golf course architecture. Yet without instinct and randomness, great design can not be achieved. Routing and designing a great golf course is all about following the lead nature provides and adapting the natural attributes of a piece of ground to golf. The randomness of nature is what produces the vast palette of landscapes on this planet, whether for golf or other uses. The only way to translate that randomness to golf is through instinctual design decisions and not calculating, repetitive thought processes which lead to formulaic design. I am a very instinctual designer who strives to develop randomness in my designs. Through these efforts, the diversity of nature will be reflected in a variety of strategies and golf forms. Strategy is not a black and white decision-making process. In fact, it is that gray area in between which all great golf holes possess. The random placement of hazards and incorporation of land forms ensures that different choices will be presented to the golfer. By following instinct, I am able to maximize this randomness and, in turn, create a golf course routing and design which maximizes the ground upon which it sits. The end-products to my clients are timeless interest and challenge, and more importantly, repeat play.

Variety

In describing great golf course sites (before or after construction), the common denominator that all great sites and courses possess is variety. A variation in topography far outweighs sprawling sand bunkers and acres of water. Money and earthwork can not replace the variety of land forms that come from nature. Knobs, knolls, plateaus, swales, saddles, hollows, and ridges stretching across a piece of ground are the features all the great courses of the world possess.

Strategy

All great golf courses possess a variety in strategy as well. Strategy can simply be defined as the utilization of hazards (undulation, sand bunkers, water, etc.) to challenge a golfer's thought process more so than penalize a golfer's physical limitations in beating par. Strategy is not something which should be placed within a golf hole based upon the architect's whims or memories of past design work. The lay of the land must be the determining factor for the location of a hazard, and in turn, a golf hole's strategy. It is the ground between the land forms (ridges, saddles, knolls, plateaus) which reveal strategic or heroic design opportunities. These opportunities come in the form of hazards. My primary tenet when discussing strategy and hazards is that hazards are to challenge the golfer (strategy), not penalize the golfer (eye candy).

Although sand bunkers are the most common hazards utilized by golf course architects, too many can increase construction costs, maintenance costs, and difficulty. Their proliferation can decrease enjoyment of the game as well. Little talent is required for the over-placement of sand bunkers and a zealous designer can bring on disastrous results for a client.

The sign of a truly talented golf course architect is in the use of undulation as a hazard. This is best accomplished through the inspiration of the ground. The ability to uncover subtle rolls, hollows, plateaus, ridges, and natural mounds in the form of challenge for the golfer is what sets the great architects (and their playing fields) apart from the rest. Challenge is what all golfers, regardless of ability, seek out in a test of golf. Undulation inspired from the ground is the one hazard which is challenging, yet fair, for all.

Strategy is the soul of the game of golf and without strategy a golf course may be a "walk within nature", but nothing else. From an economic standpoint, strategy designed correctly equates to challenge for the golfer which equates to a variety of options for the golfer to make choices. Variety in strategy is the component of design that elevates the best work and when a site's natural features dictate that variety, it will have few rivals. The variety of choice is what creates memorable experiences and repeat play.

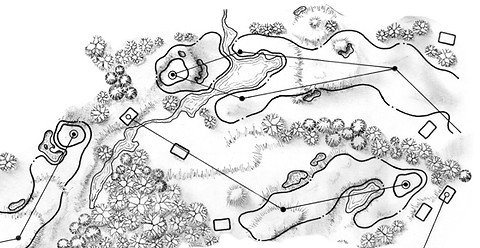

The Routing Process

My routing philosophy is based upon routing golf holes from high point to high point to high point. In other words the tees, landing areas, and greens all are located on high spots, allowing natural drainage patterns uninterrupted flow in non-play areas. This is built-in surface drainage and the result is a minimum of seasonal wet areas, less cost in re-directing drainage and less earthwork in order to make golf course features visible. This is how the great architects of the past routed such natural-appearing layouts, truly allowing the site to dictate the golf.

When first visiting a site to begin the routing process, I will walk the property with a topographic map in hand, but not without studying that map in extreme detail. Study of a golf course site not only includes physically walking the property, it also requires some feasibility work on paper as well. Without spending time analyzing the overall shape of the property and understanding the constraints of specific areas (determined either by property lines or topography), laying out a golf course strictly by site will become counter-productive at a certain point. By knowing how many holes can fit in a certain area or how the sequencing of golf holes will be affected by the overall site characteristics or environmental constraints ahead of time, I can spend much more quality time seeking out the site-specific land forms that contribute to strategy of a golf hole with the full confidence these ideas are achievable. There is no need to move dirt to create strategy.

Eighteen stakes on a Sunday afternoon is a romantic notion, but it is a bit antiquated and not very cost effective. Those critics who decry the use of topographic maps and some work on the drawing table before walking a site minimize the importance of spatial design and efficiency with one's time. Yet this should not be confused with one who routes a golf course without ever leaving the office.

This brings up one thought regarding construction documents. A myth in the golf course design and construction business is that the great architects create in the field, spending hour upon hour becoming one with the land. The supposed result is a world-class golf course. In reality, the result is probably an over-budget project. I spend numerous hours on site, but with detailed construction drawings under my arm. There is not that much talent in spending all day with a shaper in the field developing a golf hole. The real talent is walking a raw site, envisioning a golf hole, taking that vision out of my head and putting it on paper so that others can share that vision and then take it off the paper and properly implement it on the ground. If my ideas are properly formed before the bulldozers are running, I can concentrate on the details that make a golf feature fantastic and be less concerned if that feature will work without breaking my client's bank. Great design does not require an excess of money.

The Final Word

By allowing the site to dictate the golf, one can successfully capture the character of the ground, minimize costs, and maximize success. Successful golf course design is ensuring that each golf hole has strategic merit. When the land helps develop that strategic merit, the project will be elevated to the highest level of golf course design. Remember that the majority of great golf courses were built because of an excess of talent and great land, not an excess of money.